The Indian Ocean Risk

The Indian Ocean Risk During the wars of the French Revolution (1792–1801), the British East India Company conquered Sri Lanka, known as Ceylon to the British. Fearing Napoleon’s possible arrival in the Indian Ocean, the British moved into Sri Lanka from India when the Netherlands fell under French control.

Throughout history, nations like Sri Lanka have endured uprisings by global powers and have often become war zones. In the post-colonial era and during the Cold War from 1947 to 1991, developing nations led the non-aligned movement. This movement consisted of a group of member states that remained independent in global issues involving the United States and the USSR. With 120 member states, the Non-Aligned Movement became the largest grouping, representing nearly two-thirds of the United Nations members and comprising 55% of the world population.

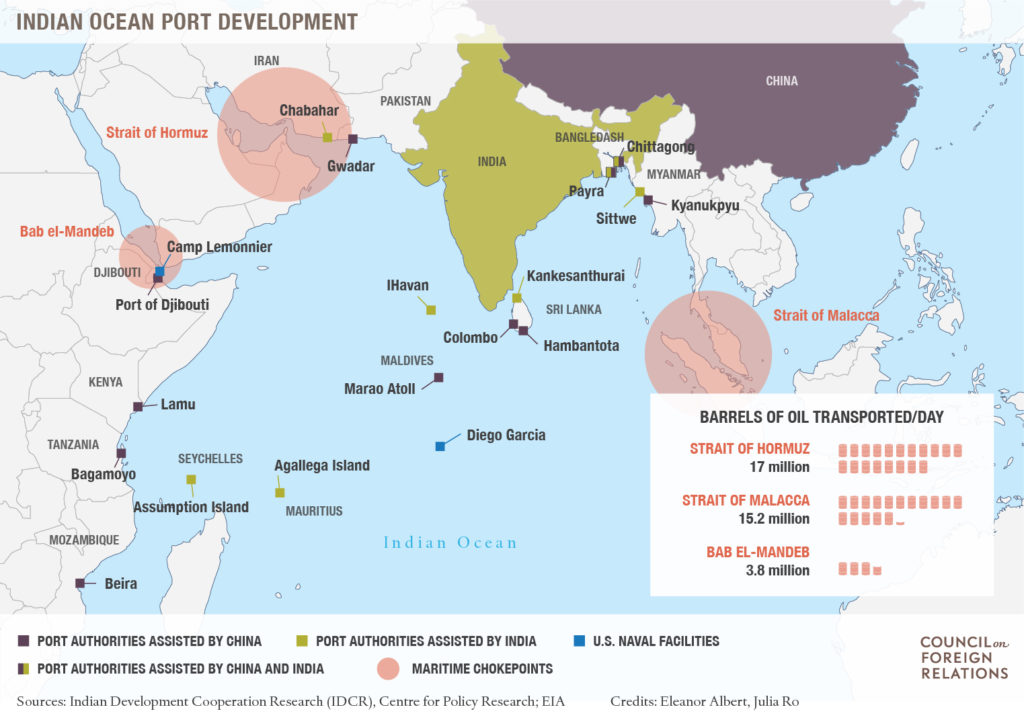

The current development of China and India, as well as the growing alliance between India and the U.S./Indo-Pacific, QUAD, etc., will result in increased naval activities. Consequently, the Indian Ocean will face similar situations as the Yuan Wang 5. Presently, the U.S. and India are finalizing an agreement to repair U.S. Navy vessels in Indian ports. Meanwhile, Pakistan is expanding its military power in the Indian Ocean, and the South China Sea is plagued by ongoing disputes.

The Indo-Pacific strategy, military alliances like QUAD, and economic alliances such as the Belt & Road Initiative, BIMSTIC, etc., are expanding their focus toward the Indian Ocean. Geopolitics is being utilized to sway small nations to choose between the superpowers, putting small developing island states in the Indian Ocean in a difficult position. Similar to China’s interest in Taiwan in the South China Sea and the U.S. and Russia’s interest in Cuba in the Caribbean Sea, Sri Lanka is a strategic island in the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, Sri Lanka serves as a gateway to the Indian subcontinent, placing it in a position similar to Ukraine’s relation to Russia.

Over the past decade, Sri Lanka has faced challenges in various aspects. When developing much-needed infrastructure like the deep terminal of Colombo Port and the Hambantota Port, as well as other digital infrastructure, external pressure has been exerted by other nations. Additionally, the visits of Yuan Wang 5 vessels and other military vessels to Sri Lankan ports have increased, indicating that similar situations will occur in the future.

China is currently the world's fastest-growing economy, and economic projections indicate that it will become the largest economy in the world during this decade. The U.S. and the West are actively working to limit China's growth. Meanwhile, India aims to become a major economy by 2040. These global economic shifts will have an impact on Sri Lanka and other nations in the Indian Ocean.

The Sri Lankan authorities should exert influence within an Indian Ocean group called “The Like-Minded Group of Indian Ocean (LMGIO).” This group would include Madagascar, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Seychelles, Djibouti, Mozambique, Comoros, and a few others. The LMGIO would adopt a neutral stance concerning India-China-U.S.-Russia’s military developments in the Indian Ocean. By excluding major nations, this group can benefit from a common agenda focused on developing trade and receiving much-needed assistance from all major global powers on an equal basis.

The LMGIO would play a significant role as many island states in the Indian Ocean are more comfortable engaging with major global powers such as the U.S., Russia, China, India, and Pakistan. However, due to increasing pressure from these powers, they are not comfortable issuing statements individually. Under the LMGIO, Indian Ocean island states can enhance their military capacity, including port developments and joint agreements for expanding military presence in the region. India, as an important trade market, and China, as it transitions to a high-income country, can greatly benefit regional nations. Free trade movements in the Indian Ocean are key to meeting the needs of many like-minded states in the region, making the LMGIO an important asset for maintaining continuous engagement and trade development.

The Like-Minded Group of Indian Ocean (LMGIO)

The LMGIO would adopt an organizational structure guided by the key principles of the UN Charter, the Vienna Protocol, and the UNCLOS. Member nations would agree on common principles when dealing with major power shifts in the Indian Ocean region:

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations in the Indian Ocean.

- Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country.

- Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself individually or collectively, in accordance with the Charter of the UN.

- In the event of a dispute between global powers in the Indian Ocean, the LMGIO would maintain a non-aligned position.

- Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

- Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation in the Indian Ocean.

The LMGIO would also establish committees focusing on security, trade, and infrastructure developments. Collectively, these committees would identify the need for technology transfer, capacity building, and funding in these areas. Member nations would participate in bilateral and multilateral agreements with major economies without supporting any trade or military conflicts among advanced economies. Additionally, the LMGIO would empower small island nations in the Indian Ocean to advance their technologies, enabling them to conduct their own fact-based assessments for self-defense.

The LMGIO members represent the most vulnerable group in the Indian Ocean in the coming decades. It is crucial for them to avoid limiting trade cooperation based on global sanctions and restrictions. Moreover, the LMGIO would negotiate the UNFCCC Paris Agreement as a collective group and identify the infrastructure development needs required to address the climate crisis. Furthermore, the LMGIO should collectively establish diplomatic training and education departments in their respective state universities. These departments would implement diplomatic study models focusing on the future of the Indian Ocean, which will be the main driver behind the organizational structure of the LMGIO

The writer is an Independent Researcher On Maritime Affairs and BRI development. He graduated from Dalian Maritime University, and in 2016 he completed a Master’s Program in Environment and Natural Resources Protection Law at Ocean University of China. He is the Co-Founder of Belt & Road Initiative Sri Lanka (BRISL), an independent and pioneering Sri Lankan-led Organization, with strong expertise in BRI advice and support.

He can be reached via e-mail: info@brisl.org or Twitter – @YRanaraja